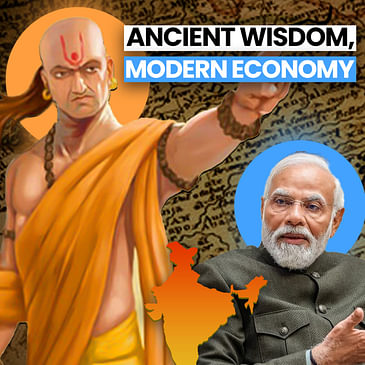

In this episode of the Bharatvaarta podcast, host Roshan Cariappa speaks with Sriram Balasubramanian, an economist, author, and contributing columnist, about the importance of understanding economic history and its relevance today. They discuss India's potential to become a $5 trillion economy and the vision for a developed nation by 2047, termed as the Amrit Kaal by the Prime Minister. Sriram offers insights into GDP growth, unemployment, urbanization, and the informal economy's role. He highlights the rich economic philosophies from India's past, especially from Kautilya's Arthashastra, and applies them to present-day economic challenges. Sriram also discusses his upcoming book that explores economic models in ancient Indian kingdoms and outlines principles for integrating ancient economic wisdom into modern policy-making, aiming towards sustainable growth and comprehensive development.

Topics:

00:00 Sneak Peak

00:54 Introduction

01:11 Unveiling Economic History's Relevance Today

03:11 Exploring Ancient Economic Principles for Modern Bharat

09:00 Applying Ancient Wisdom to Modern Economic Challenges

22:41 The Vision of Amrit Kaal: Steering Towards a Developed Economy

27:19 Understanding the Informal Economy's Role in Future Growth

30:01 Exploring the Informal Economy and Dharmic Capitalism

31:56 Policy Innovations and the Impact of Swachh Bharat

33:38 Understanding Informal Economy Dynamics and Policy Implications

34:24 Challenges of Formalization and Urban Migration

38:02 The Role of Culture in Economic Choices

39:29 Democratization of Economic Thought and Policy Making

47:27 Urbanization Strategies and Developing Tier 2, 3, 4 Cities

52:56 Addressing Employment and Job Creation

54:59 Geopolitics and India's Global Economic Strategy

57:24 Anticipating the Sequel to Kautilyanomics

_______________________

Buy Kautilyanomics: https://amzn.in/d/gKNvAZE